EDF Turns to China to Relearn Lost Art of Rapid Nuclear Construction After Flamanville Disaster

Europe’s biggest nuclear operator embeds teams with Chinese state firms to master five-year reactor timelines, racing to reorganize €73bn supply chain for France’s six-reactor renaissance after 17-year Flamanville debacle exposed catastrophic industry decline

Électricité de France, Europe’s largest nuclear operator, has launched an unprecedented campaign to reverse decades of construction competency erosion by embedding engineering teams for month-long immersions at China’s state nuclear giants CGN and China Nuclear Engineering Corporation, desperate to understand how Chinese firms routinely deliver massive reactors in five years while EDF’s Flamanville EPR took 17 years and ballooned from €3.3 billion to €23.7 billion including accrued interest. The extraordinary knowledge transfer initiative—reversing a relationship that began in the 1980s when EDF taught China nuclear technology at the Daya Bay project—underscores the existential stakes confronting Europe’s nuclear renaissance, particularly France’s €73 billion plan to construct six new large EPR2 reactors representing the region’s most ambitious nuclear project in a quarter century.

EDF executives confirmed the Chinese embeds focus intensively on supply chain parallelization, manufacturing workflow optimization, and eliminating redundant quality control checkpoints that plague Western nuclear projects. At home simultaneously, EDF suppliers convene regular coordination sessions aimed at whittling down approval stages and learning to fabricate components concurrently before final assembly commences—techniques Chinese firms mastered through relentless iteration building 27 reactors currently under construction representing 28.9 GW of new capacity.

Flamanville: Cautionary Tale of Lost Capability

The urgency driving EDF’s Chinese pilgrimage derives directly from Flamanville-3’s catastrophic construction trajectory, which became synonymous internationally with Western nuclear industry dysfunction. Construction commenced December 2007 with promises of 54-month timelines and €3.3 billion budgets—projections that proved spectacularly divorced from reality as the project hemorrhaged money and time across relentless delays.

By December 2024 when Flamanville-3 finally achieved grid connection, costs had quintupled to €13.2 billion by EDF’s accounting, or €23.7 billion including financing costs according to France’s Court of Auditors—representing seven times the original budget. The reactor reached full power only in December 2025, a stunning 17 years after construction began versus the projected four-and-a-half years, making Flamanville the poster child for everything wrong with contemporary Western nuclear projects.

The catalogue of failures proved comprehensive: design documents incomplete when construction started, forcing demolition and reconstruction of entire sections; reactor pressure vessel discovered to contain carbon concentrations 400% above specifications requiring extensive remedial analysis; eight critical steam transfer pipe welds through double-wall containment requiring robotic repairs that alone consumed three to four years and €1.5 billion; coordination breakdowns across hundreds of suppliers lacking unified project management; and regulatory interventions demanding replacement of the reactor vessel closure head shortly after startup.

France’s nuclear regulator ASN repeatedly halted work pending safety compliance demonstrations, while component suppliers—primarily Framatome (formerly Areva) before that company’s near-collapse—delivered equipment years behind schedule with quality defects requiring rework. A 2019 French government investigation concluded that launching construction before finalizing designs created cascading failures throughout the build, establishing anti-patterns that haunted every subsequent phase.

China’s Rapid Ascent: From Student to Master

The China that EDF now studies as exemplar represents a transformed nuclear industry from the 1980s when French engineers transferred pressurized water reactor technology to China General Nuclear at Daya Bay. That first Chinese commercial nuclear station, operational in 1994, relied entirely on EDF personnel for operational management during initial years—a dependency China systematically eliminated through aggressive domestic capability development.

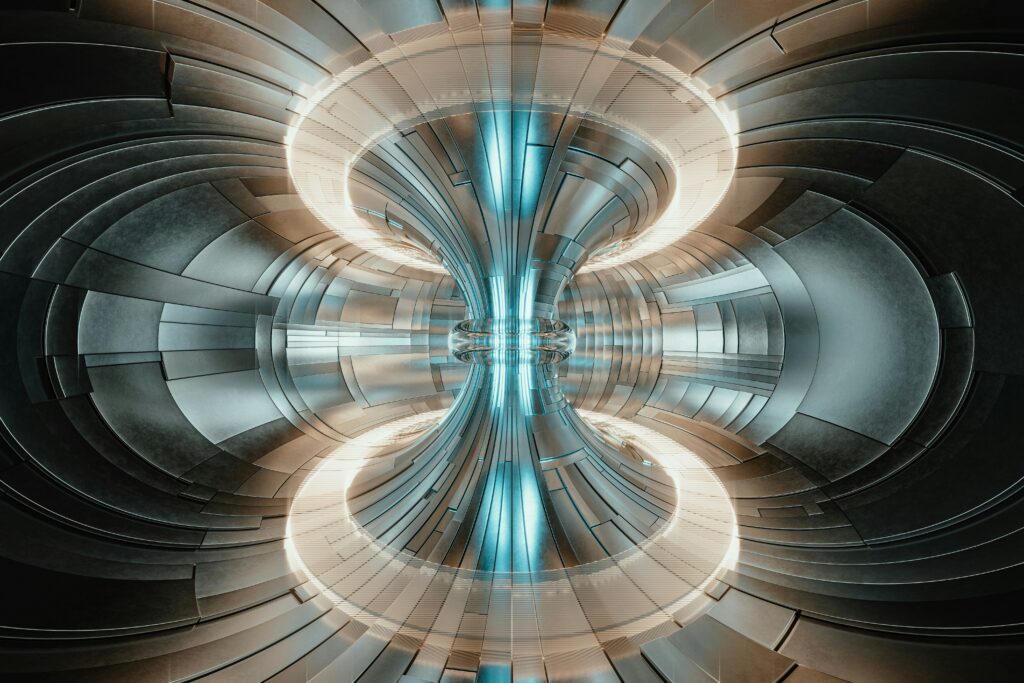

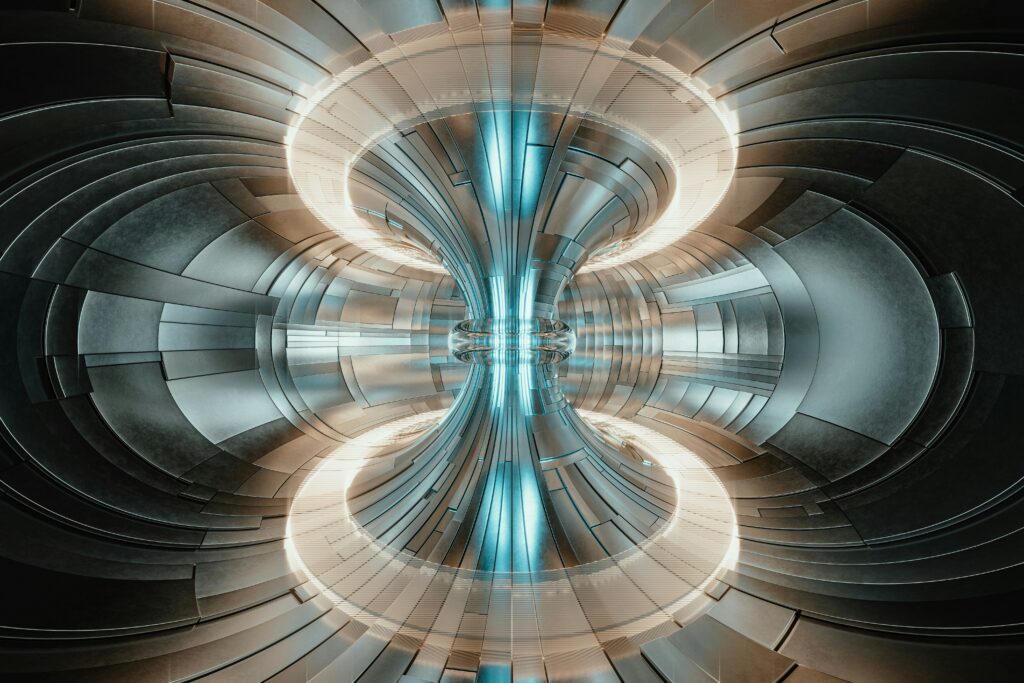

Today, China operates 56 nuclear reactors generating 54 GW with 27 additional units under construction. Chinese firms routinely complete large reactors in 5-6 years at costs far below Western equivalents. The two Taishan EPRs—identical to Flamanville’s design—commenced construction in 2009-2010 and entered commercial operation in 2018-2019 despite being the world’s first EPR completions, demonstrating Chinese execution speeds that humiliated European and Finnish EPR projects mired in delays.

China achieved this transformation through several mechanisms EDF now seeks to replicate. First, relentless standardization: China’s Hualong One reactor design, developed jointly by CNNC and CGN, became the dominant export product with streamlined approval processes and pre-certified components. Second, vertical integration: Chinese nuclear firms control complete supply chains from uranium mining through fuel fabrication, component manufacturing, construction, and operations, eliminating coordination friction across independent suppliers.

Third, regulatory coherence: China’s nuclear safety authority maintains rigorous standards while enabling parallel approval processes rather than sequential gates that create Western delays. Fourth, industrial policy backing: massive state financing ensures projects don’t halt for funding negotiations, while government mandates guarantee long-term construction pipelines allowing workforce specialization and efficiency gains from repetition.

Perhaps most critically, China embraced “learning by doing” rather than pursuing theoretical perfection. Early reactor types (CPR-1000, ACPR-1000) evolved incrementally from imported designs, with each generation incorporating lessons from predecessors. This iterative approach contrasts sharply with Western projects like Flamanville that attempted revolutionary leaps—the EPR design promised 60-year lifespans, enhanced safety systems, and 1,650 MW output simultaneously—without adequate prototype validation.

Europe’s Existential Nuclear Stakes

EDF’s scramble to recapture rapid construction capability carries implications extending far beyond French borders. President Emmanuel Macron’s 2022 announcement of France’s “nuclear rebirth”—potentially 14 new EPR2 reactors beyond the initial six—depends entirely on demonstrating cost-effective, timely construction. The first pair of EPR2s planned for the Penly site in northern France targets 2038 commissioning with subsequent reactors following at 12-18 month intervals, timelines that appear aspirational given recent performance.

The €73 billion budget (in 2020 prices, approximately €89 billion adjusted for 2025 inflation) represents unprecedented peacetime infrastructure investment concentrated in single technology. Final investment decisions initially planned for late 2025 or early 2026 were postponed to H2 2026 after France’s Court of Auditors advised EDF not to commit until designs were finalized and financing secured—lessons directly from Flamanville’s premature construction launch.

Beyond France, Europe’s broader nuclear revival hinges on credible execution. The UK’s Hinkley Point C—two EPRs under EDF construction in Somerset—faces scrutiny over costs exceeding £40 billion, while proposed Sizewell C awaits final investment amid financing concerns. Poland selected Westinghouse AP1000 designs over French EPRs, partially reflecting skepticism about EDF’s delivery capability. Finland’s Olkiluoto-3 EPR, completed in 2023, required 18 years versus the planned four years and triggered extensive litigation between TVO and Areva.

The competitive landscape intensified as renewable energy costs plummeted during nuclear projects’ extended delays. Solar and wind installations that required years to plan in the 2000s now deploy in months at dramatically lower costs per megawatt-hour, raising fundamental questions about nuclear economics when construction timelines stretch beyond a decade and budgets multiply.

Supply Chain Parallelization: The Chinese Secret

EDF’s supplier coordination sessions focus explicitly on emulating Chinese manufacturing approaches where component fabrication, quality assurance testing, and regulatory approvals proceed concurrently rather than sequentially. Traditional Western nuclear construction operates on waterfall principles: complete design documentation before manufacturing, finish manufacturing before installation, conduct comprehensive testing before next-phase authorization.

Chinese projects instead employ overlapping workflows where long-lead components begin production while detailed designs continue refinement, regulatory submissions progress during manufacturing, and installation planning occurs before all approvals finalize. This parallelization requires sophisticated risk management—changes cascade across interlinked workstreams—but dramatically compresses timelines when executed successfully.

The embedded EDF teams study specific techniques including modular construction where reactor buildings are pre-fabricated as large assemblies transported to sites for rapid installation; just-in-time component delivery minimizing on-site storage; and digital twin modeling enabling virtual assembly validation before physical work begins. Chinese firms also maintain permanent multi-disciplinary teams that transition from one project to the next, preserving institutional knowledge that Western projects lose when specialists disperse after completion.

Crucially, Chinese nuclear firms treat the initial units of new designs as learning platforms where schedule flexibility allows problem-solving without catastrophic cost impacts. Subsequent units—the “series production”—then achieve aggressive timelines based on refined processes. Western projects like Flamanville lack this luxury, with each reactor treated as bespoke prototype carrying full budget accountability from inception.

The 1980s Benchmark: When France Built Fast

EDF’s stated ambition—replicating its 1980s achievements when it “turned out dozens of reactors across France, taking roughly six years for each”—references a genuine historical capability now barely remembered. Between 1980 and 1989, EDF commissioned 35 nuclear reactors, achieving construction rhythms of 4-6 units annually with standardized designs and integrated supply chains.

That era’s success factors included government-backed financing eliminating commercial risk, dedicated nuclear engineering workforces, Framatome’s singular focus on pressurized water reactors without distraction from competing technologies, and regulatory frameworks developed contemporaneously with industry rather than imposed retrospectively. The entire French nuclear fleet deployed a handful of reactor variants (900 MW, 1,300 MW, 1,450 MW) enabling component standardization and construction team specialization.

The subsequent decades witnessed systematic capability erosion: nuclear workforce aging without replacement, supply chain fragmentation as firms diversified or exited nuclear, regulatory burden accumulation reflecting post-Chernobyl, post-Fukushima safety enhancements, and financing model shifts from state backing to commercial project finance requiring profitability demonstrations.

Recovering 1980s timelines requires not merely technical competence but institutional reconstruction—a challenge complicated by political volatility around nuclear energy. While France remains committed to nuclear baseload power, other European nations maintain phase-out policies creating inconsistent demand signals that prevent supply chain investments amortized over decades.

The Verdict on Learning from China

Whether EDF’s Chinese immersion yields tangible construction speed improvements remains uncertain pending actual project execution. Critics note fundamental differences between Chinese and French contexts: state-controlled supply chains versus independent suppliers, autocratic regulatory certainty versus democratic contestation, and massive domestic market scale enabling continuous construction versus episodic European projects.

Yet the alternative—continuing Western nuclear decline culminating in permanent loss of construction capability—appears strategically unacceptable given climate imperatives and energy security concerns. If EDF cannot demonstrate credible nuclear delivery on the six-reactor program, Europe’s carbon-free baseload power future defaults entirely to import dependence, renewable intermittency, or fossil fuel backsliding.

The stakes justify the humility of learning from former students. China’s nuclear ascendancy—from technology recipient to global leader—illustrates that capability transfer works bidirectionally. Whether EDF successfully absorbs Chinese lessons and translates them into French industrial practice will determine if Europe retains meaningful nuclear competence or cedes the field entirely to Asian manufacturers.

Further Reading

EDF delays FID on six new nuclear reactors to H2 2026 – Power Technology (February 24, 2025)

https://www.power-technology.com/news/edf-delays-fid-nuclear-reactors-2026/

Long-Delayed Flamanville-3 Nuclear Plant In France Connected To National Grid – NucNet (December 21, 2024)

https://www.nucnet.org/news/long-delayed-nuclear-plant-connected-to-national-grid-edf-announces-12-1-2024

EPR (nuclear reactor) – Wikipedia (January 19, 2026)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EPR_(nuclear_reactor)

China and France aim to strengthen nuclear energy cooperation – World Nuclear News (May 9, 2024)

https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/China-and-France-aim-to-strengthen-nuclear-energy

How Innovative Is China in Nuclear Power? – ITIF (December 16, 2024)

https://itif.org/publications/2024/06/17/how-innovative-is-china-in-nuclear-power/

The post EDF Turns to China to Relearn Lost Art of Rapid Nuclear Construction After Flamanville Disaster appeared first on European Business & Finance Magazine.