Why Weak Accountability in Albania Systematically Undermines EU Investment Flows, Market Confidence, and the Credibility of the Enlargement Process

Albania’s bid to join the European Union is quickly becoming a defining test of the Union’s enlargement credibility. It is also increasingly a question of economic governance and investor confidence, with direct implications for EU funding, capital inflows, and market stability. For years, Brussels has positioned the Western Balkans as a key frontier for extending stability, democracy, and the rule of law in Europe. But recent developments, including a high-profile case involving Tirana’s mayor, Erion Veliaj, expose deep governance challenges that the EU cannot afford to ignore.

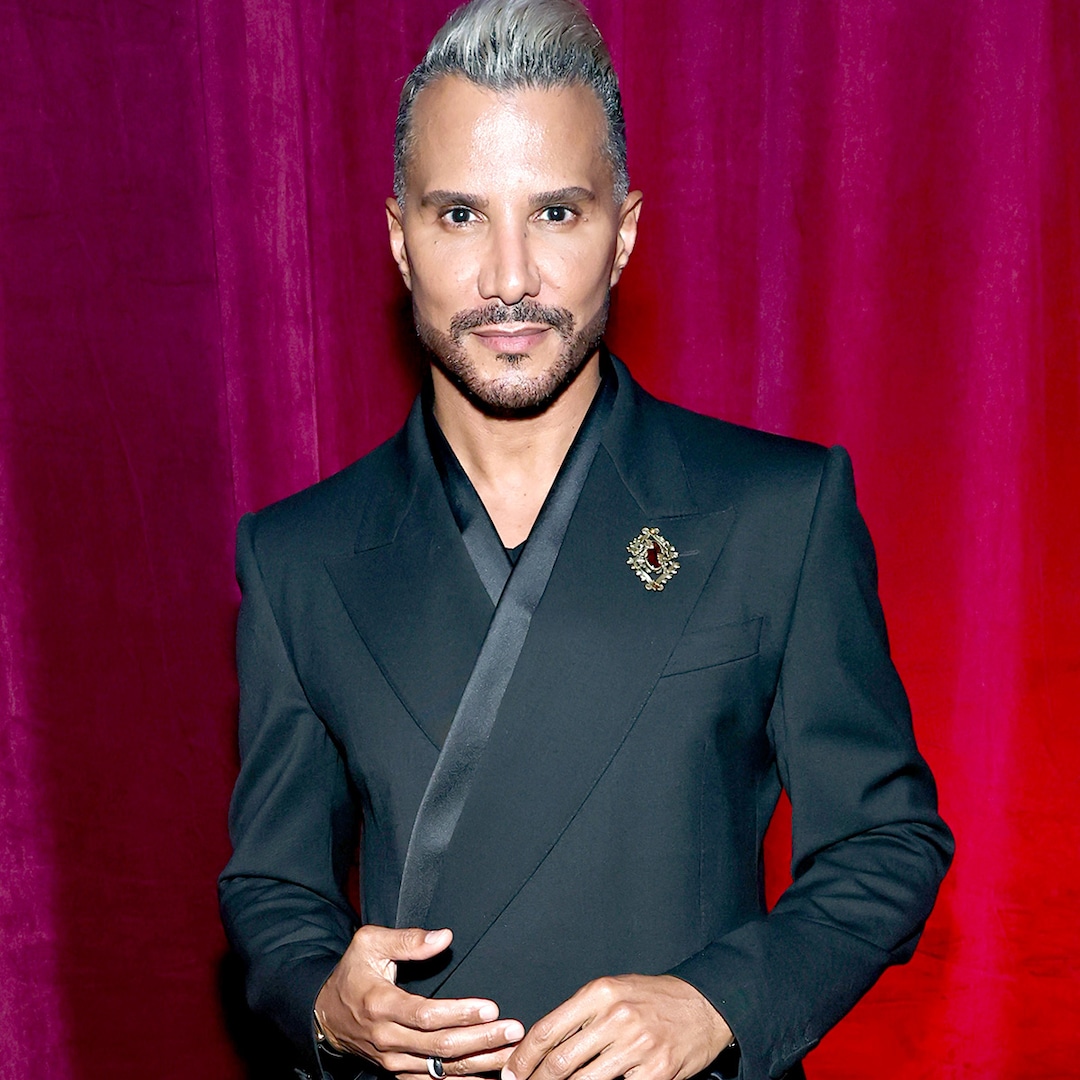

Veliaj, a three-time elected mayor of Tirana and a prominent figure in Albania’s Socialist Party, was arrested on February 10, 2025, by Albania’s Special Anti-Corruption and Organised Crime Structure (SPAK). Since his arrest, he has been held in pre-trial detention for nearly a year without formal charges being brought in a timely manner and denied bail or

meaningful access to his international legal counsel. Many have identified the arrest as a politically motivated persecution, with this prolonged detention

raising profound concerns about due process and proportionality, core European legal standards that all EU candidates are expected to uphold, and which form the basis of legal certainty required for long-term investment decisions.

From the outset, Brussels positioned Albania’s justice reform efforts as central to its accession path. These reforms were also designed to reassure EU taxpayers, development banks, and private investors that public institutions could be trusted to manage funds transparently and predictably.

Yet the handling of Veliaj’s case illustrates how anti-corruption instruments can be wielded selectively. SPAK, the very institution strengthened with EU backing to combat graft, now faces criticism for how it has managed the investigation and detention. Observers note that Veliaj’s continued incarceration, nearly a year after his arrest, and the denial of standard legal protections

undermine confidence not only in the fairness of the proceedings but in the broader legal framework they are meant to demonstrate.

This matters for the EU beyond Albania’s domestic politics. Enlargement is fundamentally a system of conditionality, where progress toward membership is tied to demonstrable reform and respect for democratic norms. That conditionality also governs access to pre-accession assistance, EU guarantees, and the credibility needed to attract foreign direct investment. If Brussels fails to raise serious concerns about the rule of law in Albania’s capital, particularly in a case with clear procedural irregularities, it risks sending a message that these conditions are negotiable. Such ambiguity weakens the EU’s leverage in enforcing sound governance and protecting the effective use of EU funds.

The Veliaj case has caused alarm among legal experts and civil society precisely because it blurs the line between legitimate anti-corruption enforcement and politically charged prosecution. Veliaj’s lawyers recently urged Albania’s Constitutional Court to expedite its review of his detention, highlighting how delays in resolving the legal challenges are harmful not just to individual rights but to the

effective administration of Tirana itself. For businesses and investors, prolonged institutional paralysis in the capital also raises concerns about municipal decision-making, public procurement, and regulatory continuity.

Even the Constitutional Court has intervened in related political decisions, reinstating Veliaj as the lawful mayor after an attempt to remove him from office

was ruled unconstitutional. These conflicting judicial signals highlight institutional strain rather than clarity.

The EU’s enlargement framework is already under scrutiny. Many member states are wary of widening the Union amid internal challenges, and support for new accessions hinges on assurances that candidate countries will not export weak governance or democratic volatility into the bloc. Albania has the highest pre-trial detention rate in Europe, and the exceptional use of detention in Veliaj’s situation raises red flags about proportionality and judicial independence, both of which are critical to maintaining predictable business environments and manageable risk premiums.

Brussels must be cautious not to fall into the trap of selective silence by praising progress in areas where it exists while ignoring glaring lapses where domestic politics cloud objective assessment. To overlook the apparent procedural issues in Veliaj’s case, or to treat them as purely internal matters, would undermine the very rationale for the Union’s enlargement policy. Inconsistent enforcement of rule-of-law standards ultimately translates into higher perceived risk for investors and weaker confidence in the EU’s enlargement framework.

Moreover, the implications extend beyond Albania. The Western Balkans sit at a geopolitical crossroads, with competing influences from larger powers seeking footholds in the region. A credible EU enlargement process strengthens regulatory alignment and economic resilience against external pressures. Conversely, a weak response to rule of law erosion in Albania could signal to both domestic and foreign actors that authoritarian tendencies and procedural manipulation carry little actual cost in the context of EU accession.

The case also resonates with citizens within Albania, many of whom have expressed frustration with the uneven application of legal standards and diminishing trust in institutions. The EU’s insistence on accountability is not just a matter of technical compliance; it is a reaffirmation of a contract with the people of Albania who aspire to join the European project. The Union’s credibility with civil society, often a crucial agent of democratic reform, depends on its willingness to confront uncomfortable realities rather than gloss over them for political convenience.

What should the EU do? For starters, it should make clear that judicial independence and due process are non-negotiable benchmarks in Albania’s accession progress. These benchmarks should be explicitly linked to financial assistance, investment guarantees, and accession-related funding decisions. Progress reports should assess not only the existence of anti-corruption bodies but also how those bodies operate in practice, ensuring transparency, proportionality, and respect for fundamental rights. Dialogue with Tirana must include measurable expectations for procedural fairness and timely judicial review, with concrete consequences if these conditions are not met.

In addition, the EU should support greater access for independent monitors, civil society, and international legal experts to observe cases of significant political import. Greater transparency would help restore confidence among European policymakers, markets, and institutional investors. Restricting oversight fuels the perception of opacity and fuels distrust among both Albanians and European policymakers.

Ultimately, the EU must demand accountability not as a punitive act but as an affirmation of the values that define it. Those values are inseparable from the economic credibility on which the EU’s internal market and enlargement strategy depend. If enlargement loses its integrity by tolerating deviations from basic democratic standards, then the promise of a Europe “whole and free” becomes hollow. Albania’s accession path should be anchored not in political expedience, but in the unwavering application of the principles that bind the Union together.

The post Albania, the EU’s credibility test: Why Brussels must insist on accountability appeared first on European Business & Finance Magazine.