Frankenstein review: Guillermo del Toro delivers a moving masterpiece of horror and romance

It's a love story as only Guillermo del Toro can tell it. For ages, the Mexican filmmaker, who has awed audiences with wondrous films like The Devil's Backbone, Pan's Labyrinth, Crimson Peak, and the Academy Award–winning The Shape of Water, has dreamed of turning Mary Shelley's Frankenstein into a movie of his own. And what he has accomplished here — notably with some of Hollywood's most beautiful men in the lead roles — is absolutely astonishing.

Ahead of the North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, del Toro explained to the audience how for him, Frankenstein is a story of fathers and sons, exploring his relationship to his own father and his own children. But audiences won't need a curtain speech to understand this inspiration point, as del Toro's script is unabashedly about the ties that bind and sometimes suffocate.

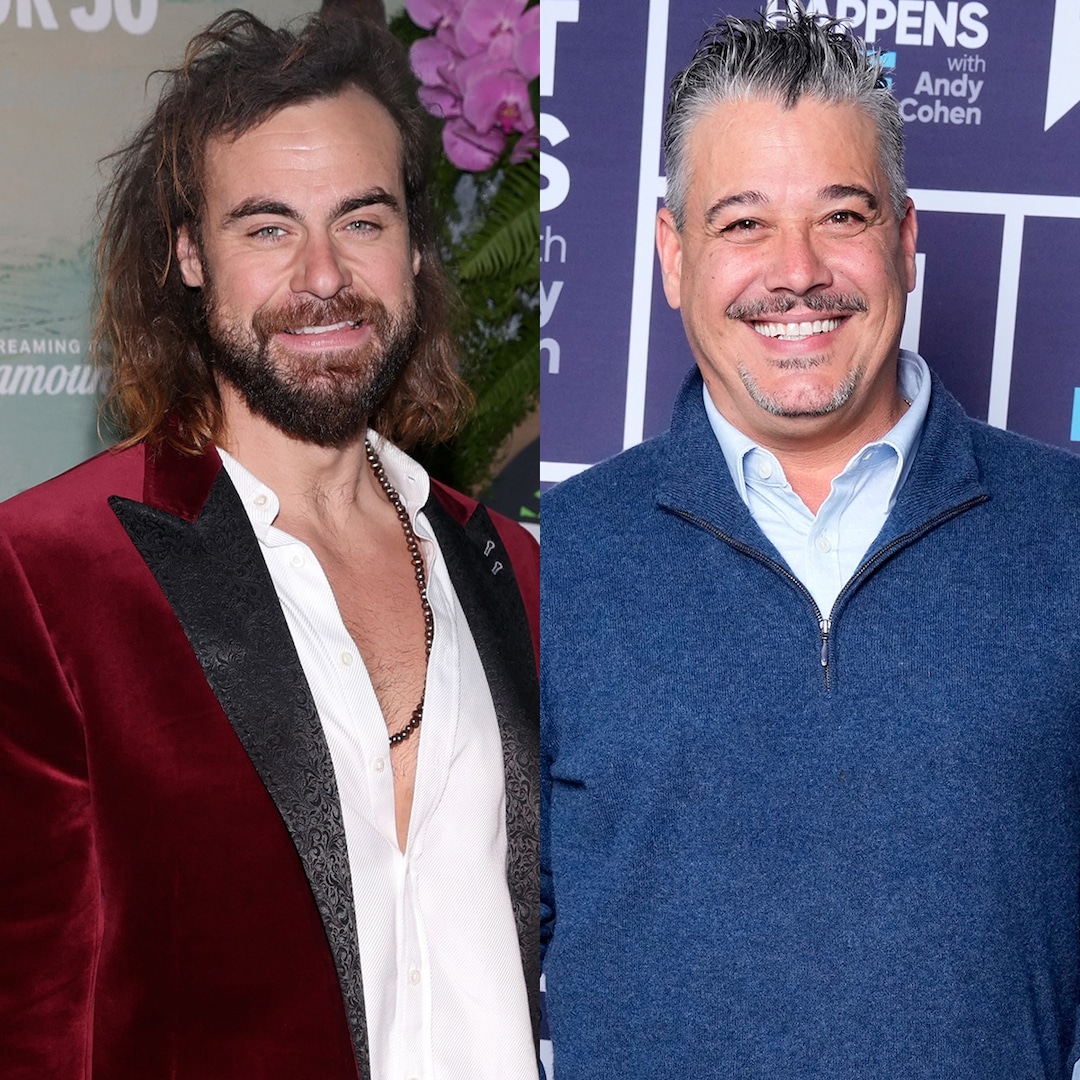

With the help of a star-studded cast that includes Oscar Isaac, Jacob Elordi, Mia Goth, Charles Dance, and Christoph Waltz, this rightly heralded writer/director resurrects a classic horror story with a romantic flair that makes it gruesome, beautiful, and deeply poignant all at once.

Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein focuses on cycles of behavior and abuse.

This version of Frankenstein begins with a framework that recalls Shelley's 1818 novel. In 1857, in "farthest north," a crew of freezing sailors chips away at their ice-seized ship as their captain hollers about reaching the North Pole. Then, they find a man, bleeding and broken, barely alive on the icy terrain.

They pull him aboard only to discover he's being pursued by a mighty, bellowing "thing." The man is Victor Frankenstein (Isaac), the thing is his monster (Elordi). After a swarm of sailors beats the latter back in a dynamic and fiery action sequence — taking heavy, grisly losses — they sail on, but Victor warns the Creature will return, and so begins his story to the captain.

Through this framework, the film flashes back to Victor's youth, where he was in a bitter battle with his cruel father (Dance) over his beautiful mother (Goth). As a boy, Victor sought the love of his mother but the approval of his father, if only to avoid the lashings the latter considered parenting. When Victor's mother dies in childbirth, he blames his surgeon father for failing, and seeks to best them both, though he only articulates his wish to outmatch his father.

Years later, as a fanatical scientist, Victor experiments with electricity on corpses, seeking to resurrect them into a new living thing. Like James Whale's iconic Frankenstein, there's the fantastical element of a man creating life without the intervention of a woman. Here, because of Victor's pronounced love of his mother, his experiment feels like a backwards way to prove she need not have died. But in a bigger way, it is to defeat death as his father never could.

His victory comes when he successfully stitches together and electrocutes to life a son. But Victor's failing is falling into the same cycle of abuse his father modeled. At first, Victor is in awe of his towering creation as it toddles in awkward steps and begins to explore its dungeon containment, splashing in puddles of water and reaching curiously for the fire that lights the space. But when his monster's intellectual development doesn't meet Victor's standards, it will be the lash, just as Victor experienced when he flunked his father's lessons.

Oscar Isaac is great in Frankenstein.

Isaac brings a frightening fire to the role of Victor Frankenstein. He is not the raving mad scientist of the Universal Monster movies. He is not the egotistical showman of Kenneth Branagh's Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Isaac makes the part his own by digging into the paternal determination to mold his "creation" in his own image.

Furthering the Oedipal thread that began in his childhood, this Victor is given a softer side through a romance subplot and a clever bit of casting. Victor becomes instantly besotted with Elizabeth, a young maiden who loves sciences and insects, and who is also played by Mia Goth.

Her girlish beauty gives an impression of innocence and gentleness, but del Toro's script bolsters Elizabeth with a sharp scientific intelligence, something she shares with Victor though their morals differ intensely. When she sees the monster, she sees someone impressive and pure, despite his scars and lack of academic accomplishment. She sees a soul that Victor cannot grasp. She becomes the foil to Victor's drive, echoing the warmth and joy of his mother. Thereby, the monster becomes a reflection of both his "father" and "mother," an accomplishment the cold, violent Victor failed to achieve.

Jacob Elordi is iconic as Frankenstein's monster.

At six feet, five inches tall, Elordi easily towers over his co-stars. But rather than sporting bolts in his neck or gnarly lumps of sullied flesh, del Toro's monster is lean and muscular, pale to the point of nearly being blue, and precisely constructed. There's a slight resemblance to the Engineers, the tall, robust, alien race from Prometheus. However, the scars along his wrists, limbs, torso, and face will never let us forget his origins.

Elordi has a difficult role because the Creature's arc is one of pain that often has no voice. Much of the performance is doggedly physical. After his birth, he is a child, though his father cannot see that. Elordi reflects this with a portrait of exploratory physicality so much like a toddler's that it's both wondrous and wretched, as we know what horrors will come next for this innocent.

At Victor's hands, the Creature experiences physical, emotional, and psychological abuse; he's chained, beaten, and insulted. Meeting Elizabeth, however, gives the Creature a greater understanding of the possibilities of the world and people. The second half of the film focuses on the monster telling his own story to the ship's captain, the framework device switching perspectives. While sound effects are employed to give Elordi's voice a harrowing, monstrous echo in these scenes, the delivery of the Creature's words as he finds his voice is bedecked with pain and earnest wonder.

The Creature's story, where he is cast out by one family and so chooses another, is one that will speak to many, especially as Elordi's crackling voice explains the heartbreaking realization that the world may try to destroy you just for being yourself. This misfit monster becomes a radiant analogy for self-love, as he is both horrid and beautiful, misunderstood and full of potential and love. For this monster, del Toro carves out a different ending from Shelley's — one that is bittersweet and glorious.

None of these risky deviations or romantic embrace of the monster would work were it not for Elordi's performance. He wears a full body of prosthetic scars and putridly pale skin, but he suffuses every movement, every glance with purpose and emotion. Escaping his well-recognized handsomeness and the expectations that come with being a dashing leading man, Elordi is del Toro's perfect monster, wretched and wondrous.

Del Toro's Frankenstein is a romantic fairy tale and a horror movie.

Like Crimson Peak, perhaps Del Toro's most misunderstood film, Frankenstein embraces a romantic fairy tale tone that urges audiences to indulge in its impressions and emotions. Because the film is told from one perspective then another, there's a suggestion that what we're shown is not what happened but how it felt.

So, a preposterous tower shoots into the sky like a dark, threatening blade, its insides riddled with rot, overrun with vines, and yet glistening with top-of-the-line tech, funded by an eccentric arms dealer (Waltz). And here, a young woman is both Victor's dream girl in intellect but also wears the face of his mother. Could that be real? Or is Elizabeth as Victor dreams her? Likewise, the violence the monster inflicts on others feels impossibly powerful, as he chucks wolves away with the slash of a forearm and rocks an ice-bound ship loose of its frigid bonds. At times, del Toro's story feels impossible, and that's precisely the point.

Every element of this film is like a fairy tale, not the kind we tell to children to help them fall asleep but the kind used in dark forests and evil-plagued eras to warn them of a world that won't see them as beautiful but as meat. So, the design of the monster follows this idea, being both splendid and scarred. The experiments of Victor's process are gruesome, but also reveal the natural beauty of human's internal design.

The costumes by Kate Hawley (Crimson Peak) are extraordinary, ranging from dark shrouds, so charred and befouled you can practically smell them, to gossamer gowns and veils that float almost impossibly, draping Goth in vibrant colors. And details along the spine of both the Creature's crusty trench coat and Elizabeth's corseted gowns remind us of the bones that lie beneath, a connection between them and their fortitude against the abuses of the world.

The score by Alexandre Desplat is sumptuous in its agony. Stringed instruments call out in longing and loss, enveloping the audience and the monster with the same, overwhelming surge of hurt and awe. The sound design as a whole embraces del Toro's signature blend of horror and romance. Sounds of violence snap and squelch, but in a symphony all their own. Across the production design, a vicious, brilliant red ties everything together, from Victor's mother (who drapes herself head to toe in the color) to his leather gloves as he operates, a book here, a funeral wreath there, and of course, in the end, blood. Yet the juxtaposition this sharp color serves against so much high-contrast blacks and whites of cloaks and dead flesh doesn't seem threatening; instead, it's a reminder of life — vibrant, pulsing, and unstoppable.

As a whole, del Toro's Frankenstein is a marvel. His vision is clear and mesmerizing. His ensemble is electrifying. His adaptation is unique, soulful, and unforgettable. The man who loves monsters has just made his masterpiece: It's rich, rapturous, and ruthlessly interrogates what it means to be human, with all of our glory and our flaws.

Frankenstein was reviewed out of its North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. The movie will open in select theaters in Oct. 17 (and this critic suggests you go see it big!). A Netflix release will follow on Nov. 7.