Cyber Security in an Era of Hybrid Warfare: Insights from Sir Mark Lyall Grant

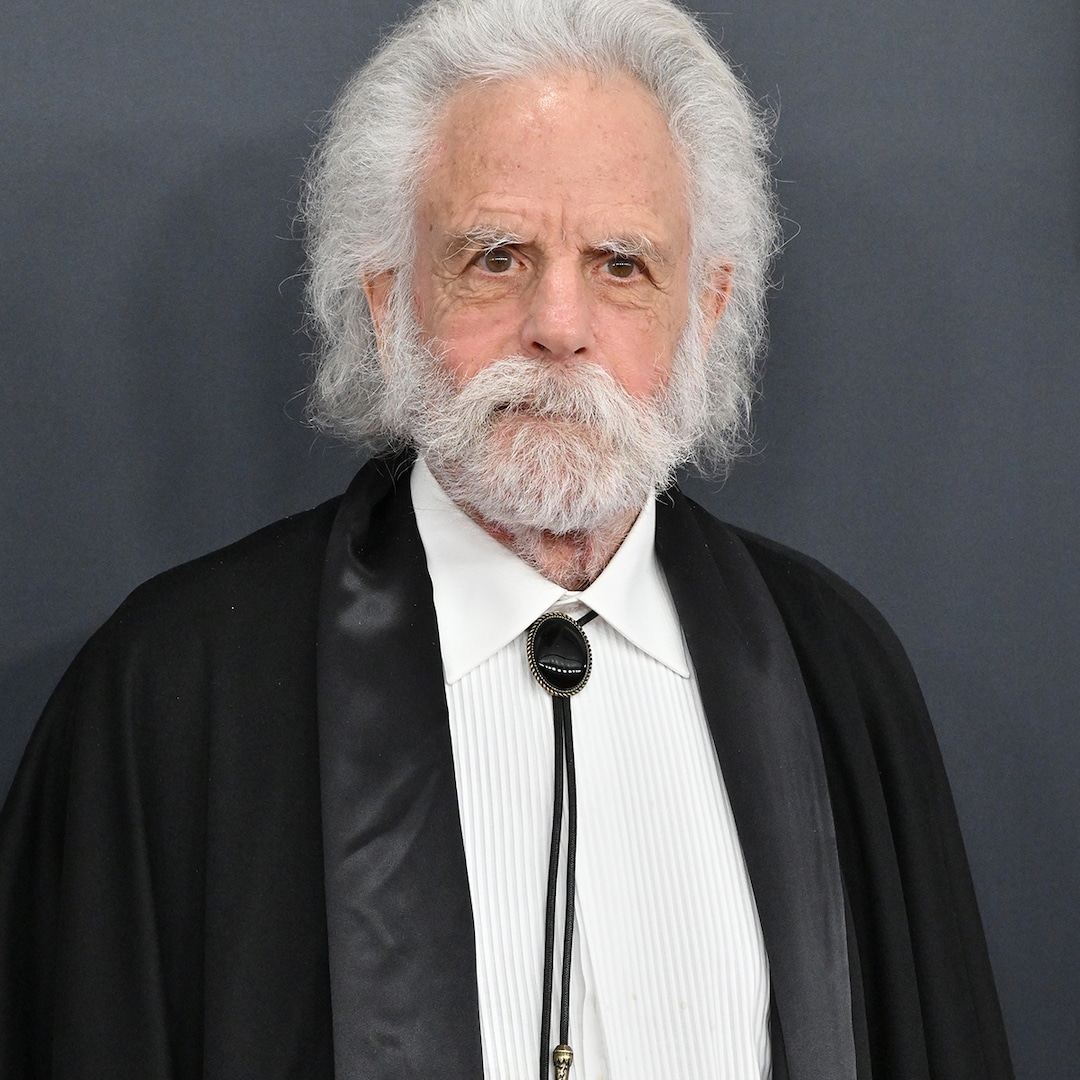

Sir Mark Lyall Grant is one of the UK’s most distinguished cyber security speakers, bringing decades of frontline experience in national security, international diplomacy, and intelligence strategy to the global stage.

Sir Mark Lyall Grant is one of the UK’s most distinguished cyber security speakers, bringing decades of frontline experience in national security, international diplomacy, and intelligence strategy to the global stage.

As the former UK National Security Adviser and Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Sir Mark has operated at the highest levels of government during pivotal moments in modern history.

With deep insights into cyber warfare, hybrid threats, and global power dynamics, he delivers unparalleled perspectives on today’s most pressing security challenges—making him a leading voice for organisations navigating the complex intersection of technology, geopolitics, and defence.

Q: The term ‘hybrid warfare’ has gained significant traction in modern geopolitical discourse. From a national security perspective, how would you define it, and what forms does it typically take in today’s global landscape?

Sir Mark Lyall Grant: “Well, the big nations in the world—the main powers—are not actually at war with each other and haven’t been, obviously, for several years. But that does not mean that they’re at peace. We’re in a sort of stage at the moment of what some people call a hot peace or hybrid warfare. What that means is that, whereas we are not directly fighting against our enemies, we are doing so in different ways.

“So, hybrid warfare can include, for instance, cyberattacks. It can include information and misinformation campaigns. It can be proxy support—like the Western military support for Ukraine, if you like. Assassination attempts overseas, using mercenaries like the Wagner Group to undermine the United Nations and Western countries in Africa, as the Russians have been doing.

“All these are elements of hybrid warfare in that sort of grey zone between war and peace, which is why the intelligence agencies of all the major powers have become even more important in today’s security world than they were before.”

Q: In your direct dealings with global heads of state—from Vladimir Putin to Xi Jinping—have you observed any recurring characteristics or leadership behaviours that transcend political systems and national cultures?

Sir Mark Lyall Grant: “Well, I’ve met most of the important world leaders of today—whether that’s President Putin, Donald Trump, Xi Jinping of China. I think it’s difficult to say that they all have similar characteristics, because they’ve all come to power in different ways, and they all come from slightly different backgrounds.

“But if we look at politicians and leaders more generally, particularly in the United Kingdom, I have found during my long association with politicians that they generally have two traits in common.

“One is a very high sense of self-worth. If you’re putting yourself up for election, or even if you’re conducting a military coup, you think that you have something to offer your country or the world. So, a very high sense of self-worth.

“The second—and this is particularly true of the United Kingdom—is that all politicians have a gambling streak. I think this partly goes down to the fact that politics is a very hazardous business. One minute you’re in power, next minute you’re not in power.

“You can lose your seat and lose your career as a result. I’m never surprised when politicians are caught on Hampstead Heath with their trousers down or something—because they have that sort of gambling streak. They know that their careers are potentially short-lived, and we’ve seen that in many leaders in this country, but also overseas.”

Q: Having served as both Ambassador and National Security Adviser, how has the nature of diplomatic engagement evolved over the span of your career—particularly in light of technological and geopolitical shifts?

Sir Mark Lyall Grant: “Well, clearly the environment in which diplomacy takes place has changed very significantly over the last 40 to 50 years. How could it not, given the technology, the transport revolution, which means that not only can leaders talk to each other directly whenever they want, but they can also travel overseas to meet each other whenever they want.

“One striking statistic is that in the first 170 years of the existence of the United States, the US President and the British Prime Minister met only once. But from 1940 onwards, for the next four years, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt met 11 times in eight different countries. So, that sort of technological change, transport change, allows politicians and leaders to meet directly without necessarily going through their ambassadors overseas.

“However, despite the fundamental change in the environment, what diplomats actually do today hasn’t changed in the last 100 years. There are four main tasks for a diplomat:

“There’s the political task—getting to know your country, who are the key decision-makers, how do you influence them, and you give advice back to your own government on those issues.

“You’ve got the commercial role, which obviously is extremely important, particularly in countries like Singapore or the United Arab Emirates. It’s probably the most important diplomatic role in countries like that.

“You also have the representational role, and that is extremely important. If you’re a British Ambassador, you’re not the government’s ambassador—you’re His Majesty’s Ambassador. That nomenclature reflects the fact you’re representing the state as a whole: the United Kingdom. When it comes to the United Kingdom, what does that mean?

“That means things like the history, the economy, the English language, the culture, the Royal Family, the Premier League, the elite universities, and the Special Forces. It’s all those things about the United Kingdom that foreigners think about when they’re thinking about the UK. That’s what an ambassador is representing overseas.

“And then the last task—and probably what many members of the public will consider the most important task—is consular work. Looking after your own nationals when they get into trouble, when they’re arrested and put in prison, when they have an accident, when they lose their passport, when they are forced into a marriage or something like that.

“Lots of different examples I could give of the sort of consular work that ambassadors do overseas. So, although the environment has fundamentally changed over the last 40 to 50 years, what a diplomat actually does hasn’t fundamentally changed.”

Q: You’ve had a front-row seat to global diplomacy. What do you aim to leave audiences with when speaking publicly on foreign policy and national security?

Sir Mark Lyall Grant: “Well, I hope that my speeches are both informative and entertaining. Above all, what I always try to give an audience is a better understanding of the inside politics—inside foreign policy, inside geopolitics.

“Because in a sense, I’m the person in the room. I can give a practitioner’s account of what really happens when a British Prime Minister meets President Putin or meets President Xi, for instance. It’s giving that sort of insider, practical experience and insights, which I think audiences find valuable.”

This exclusive interview with Sir Mark Lyall Grant was conducted by Mark Matthews.

The post Cyber Security in an Era of Hybrid Warfare: Insights from Sir Mark Lyall Grant appeared first on European Business & Finance Magazine.